On November 12, 2018, delegates from 150 countries — all signatories to the Montreal Protocol met on the final day of the 30th Meeting of the Parties (MOP) in Quito, Ecuador. They could afford to be pleased because they had unanimously adopted a decision to strengthen the enforcement mechanisms of the Protocol, one of the most successful global multilateral environmental efforts ever taken.

The accord entered into force in 1989, with the intention of protecting the ozone layer by phasing out the chemicals that deplete it. Nations collaborated to enforce this and the ozone layer started recovering.

The decision to strengthen the enforcement this year was taken because of an unexpected rise in global emissions of the banned chemical trichlorofluoromethane or CFC-11 and mandated all the 197 parties to provide the latest information on CFC-11 emissions and potential sources, as well as a global review of enforcement measures. Practicalities for the Kigali Amendment, which is set to enter into force on January 1, 2019 were also negotiated. This Amendment is meant to ensure avoidance of 0.5C of global warming by the end of the century and for countries to cut projected production and consumption of climate change-inducing hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) in refrigerators, air conditioners and related products by more than 80% over the next 30 years. It has so far been ratified by 60 parties.

The latest Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion has not only revealed that the ozone layer is healing but also underlines the global warming reduction potential and options for more ambitious climate action of the Kigali Amendment.The Montreal Protocol highlights the power of global cooperation, and the decisions taken at the end of the latest meeting underscore that complacency is not an option. This is why the Protocol has been successful.

Unfortunately, these somewhat positive findings have coincided with dire warnings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which indicated in a key report published in October that humanity just has 12 years to limit global warming to 1.5C. After this period, a further rise in global temperatures will result in extreme impacts on humans and ecosystems. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) revealed on November 20, 2018 that greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere have reached record high levels and there is no sign of this trend being reversed at this stage. The WMO’s Greenhouse Gas Bulletin has further shown that average concentrations of carbon dioxide (CO2) reached 405.5 parts per million (ppm) in 2017, up from 403.3 ppm in 2016 and 400.1 ppm in 2015. Concentrations of methane and nitrous-oxide also rose, and there was that resurgence of CFC-11 highlighted by the Montreal Protocol MOP. Although weaknesses in the ozone layer have meant more precipitation over the Antarctic — partially mitigating ice-sheet loss — this has been more than offset by ice-sheet calving and melting due to warming oceans.

There has been a 41% increase in the warming effect on the climate since 1990, 82% of which is from CO2, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). News reports in 2018 were replete with temperature records being shattered, sea-ice shrinking and extreme weather events devastating every continent in one of the hottest years on record. The key result of the WMO report is that 2018 is the fourth hottest year on record, in terms of average global temperature (2016 is still the hottest, followed by 2015 and 2017). The top 20 hottest years have all taken place within the last 22 years. This is pretty clear indication that we have already messed up the climate.

The global average temperature for the first 10 months of 2018 was almost 1C above pre-industrial baseline (the average between 1850 and 1900), using 5 independent data sets. The WMO Statement on the State of the Climate is in agreement with the IPCC report, as well as the US government’s Fourth National Climate Assessment released in late November 2018 (and which President Trump has refused to believe).

“The last time the Earth experienced a comparable concentration of CO2 was 3–5 million years ago, when the temperature was 2–3°C warmer and sea level was 10–20 meters higher than now,” said WMO Secretary-General Petteri Taalas.

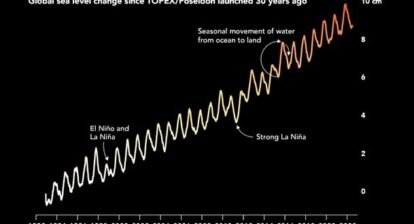

The IPCC has clearly and vociferously urged in its Special Report on Global Warming that global net emissions of CO2 need to fall by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030 and MUST reach zero by 2050 in order to keep temperatures below 1.5C. Keeping temperatures below 2C (and closer to 1.5C)is the only way to reduce the risks to human well-being, ecosystems and sustainable development. This does not mean we won’t see any impacts. We have reached the 1C mark and with that have come more extreme weather, rising sea levels, and diminishing Arctic sea ice. In fact the Arctic has been warmer in the last five years than at any other time since 1900. It went through its second warmest air temperatures and second lowest sea-ice coverage in 2018 and this has meant unusual conditions in the south.

However, the urgency of the issue has not been able to result in any concrete steps from countries. Most of them are meeting in Katowice, Poland for the 24th Conference of the Parties (COP) of the United Nations Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), from December 2–14, 2018. On December 8, the parties failed to adopt IPCC’s key report.

This year’s conference was seen as the most important since 2015, when the Paris Agreement was signed. But a lot has changed since then. The US under Trump is no longer on board and some others, reliant on fossil fuel sales, have followed suit by not completely accepting IPCC’s findings. Just a few weeks ago, Brazil under its new government, withdrew its offer to host the United Nations Climate Conference, the COP25, next year citing budget constraints and presidential transition. Developing countries have their own economic and social issues.

COP 24 is going to continue till December 14, so to answer my question in the headline: well, we did not really fix the ozone layer (CFC-11 is still there) but we did make a difference. Global cooperation and collaboration meant that we almost fixed it and the understanding that we cannot be complacent about it means that we may very well see this one through.

As I said before, the key to the success of the Montreal Protocol was global multilateral collaboration and solidarity and that is what is needed for climate change. The world needs an ambitious, multilateral, collaborative effort to implement different aspects of the Paris Agreement: developed countries providing the promised financial and technological assistance to developing nations and for developing nations to ensure transparency and commitment in their promises to cut emissions.

Parties at COP 24 need a similar kind of impetus that was present in the 1980s for the Montreal Protocol; the same commitment and dare I say, a stronger sense of morality. The problem is that those efforts were relatively easier; CFCs were not very hard to let go of. The Paris Agreement has bigger problems: fossil fuels trump everything else. In the final couple of days for COP 24, I do not see any progress in our commitment to contain climate change. This, at a time when we cannot afford to be complacent about our future.

[UPDATE]: At the end of the climate talks, after two weeks of wrangling, countries have agreed to a set of rules to help curb global warming. In essence, they have come up with a ‘Paris Rulebook’. The question is: is this rulebook to put the Paris Agreement on an effective path to mitigate climate change and help countries adapt to it enough? Some issues were sidelined, especially those that would have accounted for pollution. How and when finances would be transferred from rich to poor countries for adaptation was also disputed. And the climate science presented in the IPCC report was not universally accepted. Countries “welcomed” the report but not the findings. So, the urgency for climate action was not underscored and only the minimum level of consensus and action was accepted.

So, perhaps Greta Thunberg was right: “You are not mature enough to tell it like it is,” the 15-year-old activist from Sweden, said in the speech before negotiators. “Even that burden you leave to us children.”