Video on the Hapsburgs who ruled Europe for hundreds of years

I hope you enjoy the show. You can subscribe to the You Tube Channel for more on science, history and nature and please do check out the website and follow on social media: Twitter // Instagram // Facebook // Reddit // Tiktok. Please subscribe to the audio podcast on: Apple Podcasts // Stitcher // TuneIn // Spotify

Blogpost/Transcript

We’ve all heard of famous empires like the Roman, Moghul or the Ottomans. There is another royal family, probably not as well-known as the rest but who were extremely influential. After all, the assassination of their Archduke was the catalyst for the First World War. I’m talking of the House of Hapsburg, an initially nondescript family from the mountains of Switzerland, that rose up to become rulers of the Austro-Hungarian and Spanish Empires, and of various other parts of Europe for 700 years. I find these guys extremely fascinating, not least because of their insistence on marrying within the family, which resulted in some interesting ailments and deformities, but also because of the names by which they came to be known.

Who were the Hapsburgs? As I said before, they were one of the most influential royal houses in Europe. Not only did they occupy the throne of the Holy Roman Empire for about 300 years, they also ruled over Spain, Portugal, Bohemia, Austria, Hungary, Croatia, and several areas of the Netherlands and Italy, as well as over Spanish colonies in the Americas.

Little known fact: the Philippines is named after King Philip II (the one who married Queen Mary of England) and who was a Hapsburg. And because of his marriage to Queen Mary, he was also King of England.

They started small though. The story goes that the name Hapsburg is derived from the castle of Habichstburg or Hawk Castle, overlooking the Aar River in Switzerland. It was built in 1020 by Count Radbot and his brother in law Werner, Bishop of Strasbourg. Radbot’s son Otto II was the first to take on the name Hapsburg and added Count of Hapsburg to his title.

From their relatively small beginning in the early 11th century the family gained momentum, primarily through politically beneficial arranged marriages, and also by gaining other political privileges, such as count-ships. By the 13th century, they had stepped into high positions in the church too and in 1273, when Rudolf IV became Rudolf I as the Roman German King, he moved the family seat to the Duchy of Austria, which they ruled till the end of the First World War in 1918.

In 1452, the Hapsburgs added the Holy Roman Empire to their repertoire, with the crowning of Fredrick III as Holy Roman Emperor by Pope Nicholas the fifth. Continuing with the practice of politically motivated marriages, Fredrick arranged the marriage of his son Maximilian to Mary of Burgundy, thus eventually acquiring ruler-ship over the low countries (basically, Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium). Maximilian’s son, Philip the Handsome, became ruler of Burgundy in 1493.

Philip was then married to Joanna the Mad of Castile, who was the daughter of Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain — famous for defeating the last vestiges of Andalusian Muslim rulers and implementing the infamous Spanish inquisition. Joanna was a bit of a rebel against her parents Catholicism and her mother was not happy about it, punishing Joanna brutally for what she termed was heresy. Her father later on had her termed insane, so that she would not be able to rule Castile, which is why she got her moniker. As a child, she was known to be highly intelligent. As an adult, she was constantly controlled or confined by the men in her family, and the story of her madness remains controversial.

Joanna and Philip had 6 children and the eldest became Emperor Charles V. He not only inherited Austria, the low countries and Southern Italy but also Castile and Aragon and with them he become ruler of the Spanish colonies in the Americas. By this time, Hungary and Bohemia had also been added to the dominions, again through marriages. By the time Charles V took over in 1519, the Hapsburgs had become a world power, ruling an empire on which the sun never set because it was so extensive that at least one part of their territory always had daylight.

Charles V ruled till 1556 and then he abdicated, splitting his territories between his son Philip and his brother Ferdinand, dividing it in the Spanish and Austro-Hungarian lines. Philip got the Spanish side and became King Philip II of Spain and its colonies (including those in America and the Philippines), while Ferdinand I became King of Bohemia, Hungary and Archduke of Austria, as well as Holy Roman Emperor.

The Hapsburgs are most famous for inbreeding because they frequently married cousins and even nieces in order to consolidate their power. This resulted in the gene pool becoming increasingly limited. The family is infamous for mental and physical deformities such as an enlarged lower jaw and an extended chin (known as the Hapsburg jaw), a large nose called the Hapsburg nose and even an outward protruding lower lip or Hapsburg lip.

A study of 3,000 family members over 16 generations by the University of Santiago suggests that inbreeding directly led to their extinction. And a new study that came out in 2019 also confirms that the infamous Hapsburg jaw was a direct result of inbreeding.

The last ruler of the Spanish Hapsburgs, Charles the Bewitched was severely disabled from birth and his genome is comparable to a child born to a brother and sister. One biographer said that his head was enormous and misshapen, and that his jaw stood out so much his upper and lower teeth could not meet; he was unable to even chew. He died without any children and with him so did the Spanish line.

In addition to inbreeding related succession crises, there were other things going on in Europe that impacted the Hapsburgs. The protestant reformation that began in Germany was causing all sorts of problems in Europe in the 16th and 17th centuries. The Hapsburgs were Catholics and did not subscribe to the Protestant agenda, especially in the Netherlands and Bohemia. Which brings us nicely to the defenestration of Prague. This was basically Bohemian resistance to Hapsburg authority. In 1617, the heir apparent to the throne, the very Catholic Ferdinand of Styria (who became Fredrick II of Austria) exerted his control over Protestant Bohemia and stopped the construction of some Protestant churches. He then had the Bohemian assembly dissolved. On May 23, 1618, four Catholic emissaries arrived at the Bohemian Chancellery to discuss this with Protestant leaders. Two of the four were deemed innocent of playing any part in stopping the construction. The remaining two accepted responsibility and awaited any punishment; which was for them to be chucked out of the window. And that’s what defenestration means. They survived the 70 foot drop mainly because they fell on a large pile of manure. This event contributed to the start of the thirty year war — a brutal religiously motivated war, resulting in 8 million deaths.

So, back to the decline of the Hapsburgs, we have inbreeding and catholic-protestant fights. Because the Hapsburgs ruled over an area up to Hungary, they had to deal with the Ottomans, who kept crossing borders from the Balkans into Central Europe. The Ottomans had already laid siege to Vienna in 1529 and then again in 1683. All of this was happening while the other European powers Britain, Dutch and French were vying for control over Europe or trying to curtail each others’ (and the Hapsburgs’) influence. As a result, alliances were fluid and kept changing as and when required. This further eroded Hapsburg hegemony in Europe. The Spanish line had to contend with France taking over its territories, and then fizzled out completely with the death of Charles the Bewitched, resulting in the Spanish War of Succession.

The Austrian Hapsburg line died out in its male heirs in 1740 with the death of Charles VI and in the last female heir of the male line in 1780, with the death of his daughter Maria Theresa. Charles VI had changed the practice of succession only through the male heir and had named his daughter as his heir by promulgating what is known as the Pragmatic Sanction (which allowed for a female heir to come to the throne). The other powers in Europe recognized this, not because they had suddenly become open-minded but because they saw this as an opportunity to further encroach upon Hapsburg dominion. Maria Theresa became a pawn in this game. By the time her father died, the Hapsburg Empire was broke, low in prestige and power, and beset by conflict within its territories.

But, this did not completely stop them. Maria Theresa faced invasion from Prussia, Bavaria and Saxony (basically from the German kingdoms to the North of Austria). She lost some territory but retained most of what her father had left. Her marriage to Francis Stephen of Lorraine turned the line into Hapsburg-Loraine, which continues to this day. Marie Antoinette — she of let them eat cake fame — was their 11th daughter. Her marriage to Louis the 16th of France again shows how marriage was used to make political allies. By the way she never said that “let them eat cake” line.

Napoleon dissolved the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, so their German territories were lost but the Hapsburgs still ruled parts of Europe, mainly Austria but also Tuscany and Modena. They benefited from the Congress of Vienna, which took place in 1814 and 15 to sort out the “French Problem” after the Napoleonic wars. The house of Hapsburg basically became the Austrian Empire, now engaged in a constant conflict with Prussia.

In 1867, in order to consolidate his control, Emperor Franz Joseph gave Hungary equal status with Austria and it became the Dual Monarchy of Austro-Hungary.

In 1878, Austro Hungarian forces occupied Bosnia Herzegovina and formally annexed it in 1908. This made Serbia angry because it wanted Bosnia for itself. In 1914, Archduke Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne was shot during a visit to the Bosnian capital Sarajevo, by a Serb nationalist. Two months later, the First World War began, leading to a complete dismemberment of the Hapsburg empire. The last emperor Charles only had Austria and Hungary to rule. He tried unsuccessfully to get out of the war but was eventually exiled to Switzerland in 1918 — the family having come full circle. He was officially deposed by the Austrian parliament in 1919 and sent into exile again to Madeira after he tried to retake the throne — where he died poor and of pneumonia. His wife Zita went into mourning and wore black for the rest of her life, till her death at the age of 96.

In 1919, when they deposed Charles, the Austrian Republic also passed the Hapsburg law, which barred any member of the family to return to Austria unless they renounced their claim to the throne. In the 1960s, the head of the house, Otto, was allowed to return after he renounced all claims. Otto’s son Karl von Hapsburg-Lorraine is the current head of the family and an Austrian politician.

For further information: The World of the Hapsburgs and The Hapsburg Family Tree

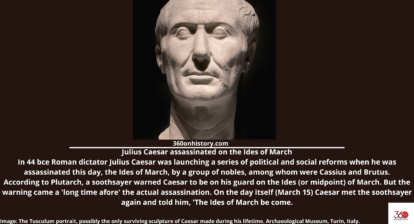

All images are Public Domain

Music: Moonrise by Chad Crouch – Instrumental from Free Music Archive.