By definition, dwarf galaxies contain stars with a total mass less than 3 billion Suns — or about 20 times less than the Milky Way. Astronomers have long suspected that dwarf galaxies merge, particularly in the relatively early Universe, in order to grow into the larger galaxies seen today. However, current technology cannot observe the first generation of dwarf galaxy mergers because they are extraordinarily faint at their great distances. Another tactic — looking for dwarf galaxy mergers closer by — had not been successful to date.

The new study overcame these challenges by implementing a systematic survey of deep Chandra X-ray observations and comparing them with infrared data from NASA’s Wide Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) and optical data from the Canada-France-Hawaii Telescope (CFHT).

Chandra was particularly valuable for this study because material surrounding black holes can be heated up to millions of degrees, producing large amounts of X-rays. The team searched for pairs of bright X-ray sources in colliding dwarf galaxies as evidence of two black holes, and discovered two examples.

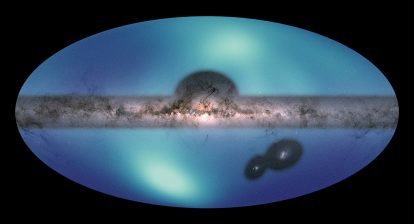

One pair is in the galaxy cluster Abell 133 located 760 million light-years from Earth, seen in the composite image on the left. Chandra X-ray data is in pink and optical data from CFHT is in blue. This pair of dwarf galaxies appears to be in the late stages of a merger, and shows a long tail caused by tidal effects from the collision. The authors of the new study have nicknamed it “Mirabilis” after an endangered species of hummingbird known for their exceptionally long tails. Only one name was chosen because the merger of two galaxies into one is almost complete. The two Chandra sources show X-rays from material around the black holes in each galaxy.

The other pair was discovered in Abell 1758S, a galaxy cluster about 3.2 billion light-years away. The composite image from Chandra and CFHT is on the right, using the same colors as for Mirabilis. The researchers nicknamed the merging dwarf galaxies “Elstir” and “Vinteuil,” after fictional artists from Marcel Proust’s “In Search of Lost Time”. Vinteuil is the galaxy on the top and Elstir is the galaxy on the bottom. Both have Chandra sources associated with them, again from X-rays from material around the black holes in each galaxy. The researchers think these two have been caught in the early stages of a merger, causing a bridge of stars and gas to connect the two colliding galaxies from their gravitational interaction.

The details of merging black holes and dwarf galaxies may provide insight to our Milky Way’s own past. Scientists think nearly all galaxies began as dwarf or other types of small galaxies and grew over billions of years through mergers. Follow-up observations of these two systems will allow astronomers to study processes that are crucial for understanding galaxies and their black holes in the earliest stages of the Universe.

A paper describing these results is being published in the latest issue of The Astrophysical Journal and is available here. The authors of the study are Marko Micic, Olivia Holmes, Brenna Wells, and Jimmy Irwin, all from the University of Alabama at Tuscaloosa.

NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center manages the Chandra program. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory’s Chandra X-ray Center controls science operations from Cambridge, Massachusetts, and flight operations from Burlington, Massachusetts.

Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of Alabama/M. Micic et al.; Optical: International Gemini Observatory/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA