Conventional wisdom regarding the evolution of medicine is that when agricultural societies emerged around 10,000 years ago during the Neolithic Revolution, previously unknown health problems also emerged. And with them arose the first major innovations in prehistoric medical practices, including the development of more advanced surgical procedures.

The oldest known incidence of a surgical ‘operation’ is thought to have been performed on a 7,000-year-old European Neolithic farmer, whose skeletal remains were found in Buthiers-Boulancourt, France. His left forearm had been surgically removed and then partially healed. If this indeed had been a sugical amputation, it would have required extensive and comprehensive knowledge of the human anatomy in addition to tehnical skill.

However, the discovery of a human skeleton from 31,000-years-ago found in Indonesian Borneo has potentially unpended this theory. The skeleton’s lower left leg is not only missing, it seems to have been surgically removed.

According to a new study published in Nature “the remains were intentionally buried in Liang Tebo cave, which is located in East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo, in a limestone karst area that contains some of the world’s earliest dated rock art”.

The remains were excavated in 2020 by a team of Indonesian and Australian researchers and archaeologists, who analysed that the amputation probably took place when the individual was a child and that he or she survived the operation and lived for another 6–9 years, before their remains were buried.

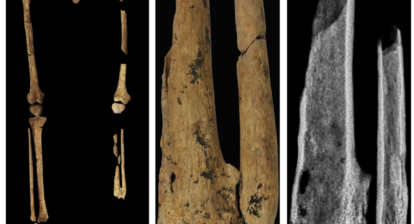

a, TB1 left and right legs with pelvic girdle, demonstrating the complete absence of the distal third of the left lower leg. b, Left tibia and fibula showing the amputation surface, atrophy and necrosis. The bone surface is more porous because lysis occurred to remove the dead bone (necrosis). c, Radiograph of the left tibia and fibula. (Maloney et al, 2022)

“This unexpectedly early evidence of a successful limb amputation suggests that at least some modern human foraging groups in tropical Asia had developed sophisticated medical knowledge and skills long before the Neolithic farming transition,” says the study. “The discovery of this exceptionally old evidence of deliberate amputation demonstrates the advanced level of medical expertise developed by early modern human foragers,” it continues.

“The Late Pleistocene ‘surgeon(s)’ who amputated this individual’s lower left leg must have possessed detailed knowledge of limb anatomy and muscular and vascular systems to prevent fatal blood loss and infection. “They must also have understood the necessity to remove the limb for survival,” the team writes. “During surgery, the surrounding tissue including veins, vessels and nerves, were exposed and negotiated in such a way that allowed this individual to not only survive but also continue living with altered mobility.”

Furthermore, they would have had knowledge of cleaning and dressing the wound, as well as other post-operative care procedures. Bony growths indicated that the “patient” was a child. There was also no sign of any infection.

Before this analysis, it was generally thought that complex surgeries were beyond the abilities of foraging societies and that they were confined to only amputation of fingers or for ceremonial purposes and as punishment.

The skeleton’s age was estimated by measuring radiation preserved in the tooth enamel, which was then matched with the results of radiocarbon dating of the burial sediment.

The researches cannot confirm whether this demonstrated that the foragers had advanced medical profiency. “Notably, it remains unknown whether this ‘operation’ was a rare and isolated event in the Pleistocene history of this region, or if this particular foraging society had achieved an unusually high degree of proficiency in this area. On the other hand, we cannot exclude the possibility that human colonization of the ancient rainforests of Borneo both prompted and facilitated early advances in medical technology that were unique to this region. For example, rapid rates of wound infection in the tropics may have stimulated the development of new pharmaceuticals (for instance, antiseptics) that harnessed the medicinal properties of Borneo’s rich plant biodiversity and endemic flora,” they conclude.

Source: Maloney, T.R., Dilkes-Hall, I.E., Vlok, M. et al. Surgical amputation of a limb 31,000 years ago in Borneo. Nature (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-022-05160-8