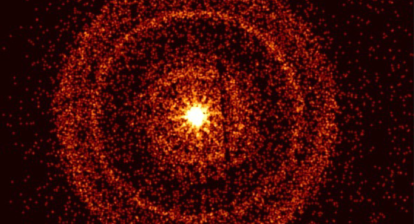

A milestone was achieved today. Nasa’s Parker Solar Probe touched the Sun. It flew through our star’s upper atmosphere – the corona – and sampled particles and magnetic fields there.

“Parker Solar Probe “touching the Sun” is a monumental moment for solar science and a truly remarkable feat,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, the associate administrator for the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Not only does this milestone provide us with deeper insights into our Sun’s evolution and it’s impacts on our solar system, but everything we learn about our own star also teaches us more about stars in the rest of the universe.” It has now traveled through the Sun’s atmosphere closer to the surface than any spacecraft before and has provided the closest ever observations of a star. (Fantastic Close up video of the Sun)

According to NASA, “As it circles closer to the solar surface, Parker is making new discoveries that other spacecraft were too far away to see, including from within the solar wind – the flow of particles from the Sun that can influence us at Earth. In 2019, Parker discovered that magnetic zig-zag structures in the solar wind, called switchbacks, are plentiful close to the Sun. But how and where they form remained a mystery. Halving the distance to the Sun since then, Parker Solar Probe has now passed close enough to identify one place where they originate: the solar surface. The first passage through the corona – and the promise of more flybys to come – will continue to provide data on phenomena that are impossible to study from afar.”

“Flying so close to the Sun, Parker Solar Probe now senses conditions in the magnetically dominated layer of the solar atmosphere – the corona – that we never could before,” said Nour Raouafi, the Parker project scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland. “We see evidence of being in the corona in magnetic field data, solar wind data, and visually in images. We can actually see the spacecraft flying through coronal structures that can be observed during a total solar eclipse.”

The Sun does not have a solid surface but does have a superheated atmosphere, made of solar material bound to it by gravity and magnetic forces. Rising heat and pressure push this material away till the point that gravity and magnetic forces are unable to contain it. That point is known as the the Alfvén critical surface and it marks the boundary where the solar atmosphere ends and solar wind begins.

As per Nasa’s website: “Solar material with the energy to make it across that boundary becomes the solar wind, which drags the magnetic field of the Sun with it as it races across the solar system, to Earth and beyond. Importantly, beyond the Alfvén critical surface, the solar wind moves so fast that waves within the wind cannot ever travel fast enough to make it back to the Sun – severing their connection. Until now, researchers were unsure exactly where the Alfvén critical surface lay. Based on remote images of the corona, estimates had put it somewhere between 10 to 20 solar radii from the surface of the Sun – 4.3 to 8.6 million miles. Parker’s spiral trajectory brings it slowly closer to the Sun and during the last few passes, the spacecraft was consistently below 20 solar radii (91 percent of Earth’s distance from the Sun), putting it in the position to cross the boundary – if the estimates were correct. On April 28, 2021, during its eighth flyby of the Sun, Parker Solar Probe encountered the specific magnetic and particle conditions at 18.8 solar radii (around 8.1 million miles) above the solar surface that told scientists it had crossed the Alfvén critical surface for the first time and finally entered the solar atmosphere.”

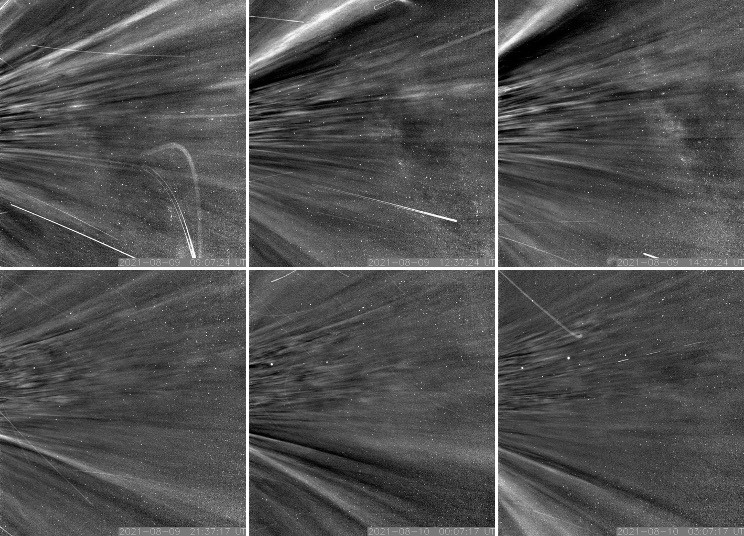

As Parker Solar Probe passed through the corona on encounter nine, the spacecraft flew by structures called coronal streamers. These structures can be seen as bright features moving upward in the upper images and angled downward in the lower row. Such a view is only possible because the spacecraft flew above and below the streamers inside the corona. Until now, streamers have only been seen from afar. They are visible from Earth during total solar eclipses.

Credits: NASA/Johns Hopkins APL/Naval Research Laboratory

“We were fully expecting that, sooner or later, we would encounter the corona for at least a short duration of time,” said Justin Kasper, lead author on a new paper about the milestone published in Physical Review Letters, and deputy chief technology officer at BWX Technologies, Inc. and University of Michigan professor. “But it is very exciting that we’ve already reached it.”

During the flyby, the Probe dipped in and out of the corona many times and provided evidence that the Alfvén critical surface is not shaped like a smooth ball but has spikes and valleys wrinkling its surface. “Discovering where these protrusions line up with solar activity coming from the surface can help scientists learn how events on the Sun affect the atmosphere and solar wind, ” accroding to Nasa.

Prior to the trips through the corona, Parker Solar Probe had already collected data pinpointing the origin of zig-zag-shaped structures in the solar wind, called switchbacks. This data highlighted that one spot that switchbacks originate is at the visible surface of the Sun – the photosphere.

The Probe also passed through a feature known as a pseudostreamer, which are massive structures that rise above the surface of the Sun and can even be seen during solar eclipses. Inside, the conditions were quieter, particles had slowed and the number of switchbacks dropped. Here the strong magnetic fields dominated the movement of particles. All these conditions provided evidence that the spacecraft had reached the Alfvén critical surface and entered the extremely hot atmosphere. This is where magnetic fields shape the movement of everything in the region.

“I’m excited to see what Parker finds as it repeatedly passes through the corona in the years to come,” said Nicola Fox, division director for the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters. “The opportunity for new discoveries is boundless.”

The size of the Sun’s corona is dependant on solar activity. The size of the corona is also driven by solar activity. As the Sun’s 11-year activity cycle – the solar cycle – ramps up, the outer edge of the corona will expand, giving Parker Solar Probe a greater chance of being inside the corona for longer periods of time.

“It is a really important region to get into because we think all sorts of physics potentially turn on,” Kasper said. “And now we’re getting into that region and hopefully going to start seeing some of these physics and behaviors.”

The Probe was launched on August 12, 2018 and in about seven years it is expected cover the (approx.) 93 million miles (150 million km) getting ever closer to the Sun, with flybys and gravity assists from Venus. According to Nasa: “The spacecraft will fly close enough to the Sun to watch the solar wind speed up from subsonic to supersonic, and it will fly though the birthplace of the highest-energy solar particles. It will trace how energy and heat move through the solar corona and explore what accelerates the solar wind as well as solar energetic particles.” All of this will not only help us to further understand stars in the Universe but also how the solar wind can affect us.

On October 30, 2018, the probe crossed the speed of 153,454 miles per hour making it the fastest-ever human-made object relative to the Sun and breaking the record set by the German-American Helios 2 mission in April 1976. It also holds the record for the current closest approach to the Sun by any human-made spacecraft (crossing 26.55 million miles). On October 31, 2018 the probe began its first solar encounter continuing to fly closer and closer to the Sun’s surface until it reached the point closest to the Sun (perihelion) for the first time on November 5.

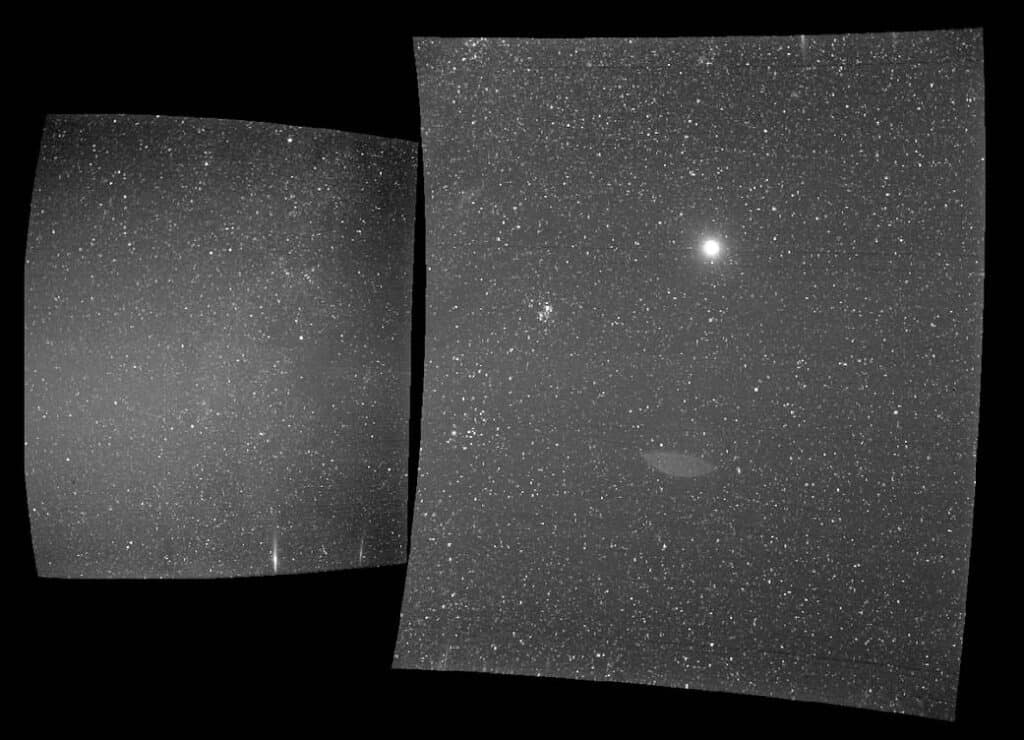

The view from Parker Solar Probe’s WISPR instrument on Sept. 25, 2018, shows Earth, the bright sphere near the middle of the right-hand panel. Image credits: NASA/Naval Research Laboratory/Parker Solar Probe

This is the first of many close approaches. The final closest approach it will make will be 3.83 million miles or 6.16 million km from the Sun in 2024, when it will also reach speeds of 430,000 miles per hour – a distance within the orbit of Mercury and seven times closer than any spacecraft has come before.

(In January 2020, The Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope produced the highest resolution image of the Sun’s surface ever taken.)

All information and images by NASA