Bloodworms are known for their unusual fang-like jaws, which are made of protein, melanin, and concentrations of copper not found elsewhere in the animal kingdom. Scientists have observed how these worms use copper harvested from marine sediments to form their jaws, and the process, described in research publishing in the journal Matter on April 25, may be even more unusual than the teeth themselves.

Because the worms only form their jaws once, they need to be strong and tough enough to last the entirety of the animal’s five-year lifespan. They use them to bite prey, sometimes puncturing straight through an exoskeleton, and inject venom that paralyzes victims.

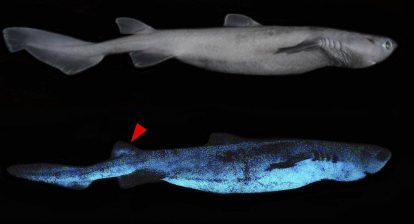

Left: Image of the everted proboscis of Glycera dibranchiata with its four jaws exposed, Right: Scanning electron microscope image of a Glycera jaw (Scale bar, 0.5 mm). CREDIT Matter/Wonderly et. al.

“These are very disagreeable worms in that they are ill tempered and easily provoked,” says co-author Herbert Waite, a biochemist at University of California, Santa Barbara. “When they encounter another worm, they usually fight using their copper jaws as weapons.”

Waite’s lab has been studying bloodworms for 20 years, but it was only recently that they were able to observe the chemical process that forms a jaw-like material from start to finish. The worm begins with a protein precursor, which recruits copper to concentrate itself into a viscous, protein-rich liquid that is high in copper and phase-separates from water. The protein then uses the copper to catalyze the conversion of the amino acid derivative DOPA into melanin, a polymer that, combined with protein, gives the jaw mechanical properties that resemble manufactured metals.

Through this process, the worm is able to easily synthesize a material that, if created in a lab, would be a complicated process involving many different apparatuses, solvents, and temperatures. “We never expected protein with such a simple composition, that is, mostly glycine and histidine, to perform this many functions and unrelated activities,” says Waite.

The team hopes that a better understanding of how the bloodworm conducts its self-contained processing laboratory could help to streamline parts of production that would benefit industry. “These materials could be road signs for how to make and engineer better consumer materials,” says Waite.

This article was first printed here. The study was published in Matter.