Almost exactly 100 years after a flu pandemic occurred in 1918, humanity experienced another one. And for over eighteen months we have been under the influence of covid19. Lockdowns, quarantine, and a shattering global economy have been the results.

But something happened that only science could bring about – we got vaccines, which have given us a ray of light at the end of this very dark tunnel. While we still have a long way to go, and there is an urgent need to vaccinate the world – especially by providing free vaccines to the developing countries – there is no doubt that we can now see a glimmer of hope that perhaps we can survive this pandemic.

I want to talk about one particular vaccine and the women behind its development: the Oxford–AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine.

When cases of a pneumonia of unknown cause started being reported in China, it was New Year’s Eve 2020 and Professor Sarah Gilbert, and Dr Catherine Green were celebrating like the rest of the world. Sarah Gilbert is a professor of vaccinology at Oxford University and co-founder of Vaccitech; Catherine Green runs the Clinical Biomanufacturing Facility that makes vaccines at the same university. By December 2020, both women had co-developed the AstraZeneca vaccine with the Oxford Vaccine Group. This was no doubt a pioneering scientific moment in recent human history and a feat of immense collaboration between thousands of scientists and others across the globe.

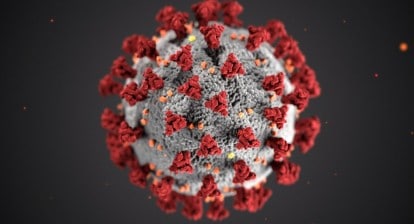

Sarah Gilbert kept a close eye on the new Sars-like virus spreading in China in January 2020. By January 10th it was confirmed that this was a novel coronavirus and Sarah Gilbert discussed the possibility of creating a vaccine with her colleague Teresa Lambe, as soon as its genetic sequence became available.

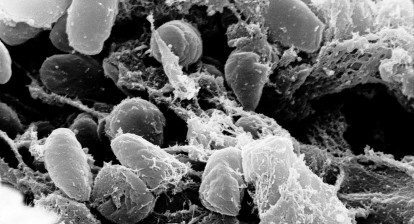

Scientists like Sarah have long predicted the eventuality of a pandemic and had been preparing for it in some ways. But lack of funding had meant that this work was going at a much slower pace. Sarah had been working on flu and MERS viruses since 2012, using a harmless, weakened version of the adenovirus (one that causes the common cold) as a vehicle to deliver proteins (or anything else) into the human body. The idea being that an adenovirus gene could be removed and replaced with one that would trigger an immune response towards a particular disease. And this technology had been used and trialled against a host of viruses and diseases for a while. What is needed is the right genetic code and if you have that, the technology was already available and the development time, as well as costs can be cut down drastically.

Although Sarah Gilbert had submitted an application to the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) to use adenovirus technology against a potential “Disease X”, she had not been able to get funding for it.

Once it became clear that a new virus had appeared with the potential to cause a pandemic, Sarah wrote to Catherine Green on the 20th of January 2020. She asked Catherine if the Clinical Biomanufacturing Facility would be able to develop the vaccine against the coronavirus, immediately. They still had no funding. But Catherine agreed.

Developing vaccines takes time requiring manufacturing trials and extensive testing to ensure safety – up to and above three years. But this was a race against time and Sarah decided to do as much work as possible beforehand, even before Covid19 became a pandemic. This was, however, dependant on the availability of the genetic sequence. So, they also continued to work along the traditional route to creating the vaccine. They used a chimpanzee adenovirus vector (ChAdOx) that generated a strong immune response to SARS-CoV-2. They used this to deliver the spike protein to trigger the immune response in the human cells.

Then on January 25, 2020, both scientists got the 100 billion dehydrated strands of the genetic code of the coronavirus protein. They started working on manufacturing and trial of the vaccine – using money they did not have yet. Oxford University ultimately agreed to underwrite a contract with Advent – the manufacturers in Italy. Other colleagues started designing clinical trials and investigating the development of the vaccine at scale, so that if needed, millions of doses could be made available.

Usually, all these processes happen step by step but now necessity dictated that all of them happen at the same time – because Sarah Gilbert had noticed something about an unknown disease in China. Over a decade of work was compressed into a few months.

By April 2020, they got the funding, without which all the preparatory work would have failed. A rapid production method was instituted involving all the protagonists – from the scientists to the administrators and the manufacturers. This was a huge career and funding risk. There were missteps, the rapid method failed, and they had to move to Plan B, which was a faster version of the traditional method. And the hard work paid off, they came up with 300 ml of the starting material, which was to be used to make the rest of the batches. They started making those first batches on March 23, 2020. The final test results were returned on April 21, 2020, and the next day the batches were certified for trial use. It had taken 65 days for them to go from DNA construction to clinical trial.

The vaccines were tested and finally in November 2020 it was revealed that the vaccine was 70 percent effective. And on December 20, 2020, it was approved for use by the UK regulator.

Obviously, this was not the only vaccine there were others more effective ones, but these were equally important and desperately needed. Extensive forethought and a lot of people coming together in a crisis resulted in being part of curtailing the human and economic costs of this new, deadly disease of our times.

False information about the vaccines as well as the blood clot issue that can potentially result from it all contributed to fuel paranoia. But the bottom line is that they vaccines work when compared to the impact of the disease they are trying to target. Science and collaboration had prevailed, and the effort has been a huge success.

The new variants of Covid are a cause for concern but we can now hope that because of the rapid, cutting-edge scientific work undertaken, we may have started to weaken its link on humanity, as long as we provide the jabs to the rest of the world as soon as possible.

As of July 6, 2021 24.4% of the world population has received at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine. 3.25 billion doses have been administered globally, and 34.81 million are now administered each day. But only 1% of people in low-income countries have received at least one dose.

Sarah Gilbert designed a vaccine for an unknown virus within a couple of weeks, Catherine Green developed that vaccine in the shortest span of time possible and led the process of its production. These are no mean feat, and their work must be acknowledged.

Sarah Gilbert was appointed Dame Commander of the British Empire and Catherine Green was given the Order of the British Empire for their exemplary work.

We may have suffered a lot over the last two years, but we also saw what humanity can do in time of a crisis. Let’s hope that in the future we won’t have to wait for a pandemic to hit before we are ready to tackle it. More investments are needed for such endeavours.

Here’s to these two pioneering and inspiring women Professor Sarah Gilbert and Dr Catherine Green and the teams that worked with them.

Images of Professor Gilbert and Dr Green from Oxford Jenner Institute - UKRI and Oxford University Website. I hope you enjoy the post and video. You can subscribe to the You Tube Channel for more on science, history and nature and please do check out the website and follow on social media: Twitter // Instagram // Facebook // Reddit. You can check out the audio podcast on: Apple Podcasts // Stitcher // TuneIn // Spotify Title music: Hovering Thoughts by Spence (YouTube Music Archive)