Discovery of crocodile “virgin birth” is fascinating but is it good for conservation?

Scientists have recently made a remarkable discovery, reporting the first-ever documented case of a virgin birth in crocodiles. The incredible finding involves a captive American crocodile Crocodylus acutus, which had been living in solitude for 16 years at a zoo in Costa Rica.

When you believe in science, the idea of a “virgin birth” sounds like a story straight from the bible. However, the phenomenon known as parthenogenesis does exist. There have been documented accounts of many animals including lizards, snakes, sharks and birds such as the California condor, hatching from unfertilised eggs.

“Over the past two decades, there has been an astounding growth in the documentation of vertebrate facultative parthenogenesis (FP). This unusual reproductive mode has been documented in birds, non-avian reptiles—specifically lizards and snakes—and elasmobranch fishes. Part of this growth among vertebrate taxa is attributable to awareness of the phenomenon itself and advances in molecular genetics/genomics and bioinformatics, and as such our understanding has developed considerably”, say the team of scientists in the study.

This is however the first case of parthenogenis occuring in a crocodile, which is extremely interesting to scientists.

According to the scientists: “The latter group [crocodiles] is particularly interesting because unlike all previously documented cases of FP in vertebrates, crocodilians lack sex chromosomes and sex determination is controlled by temperature.”

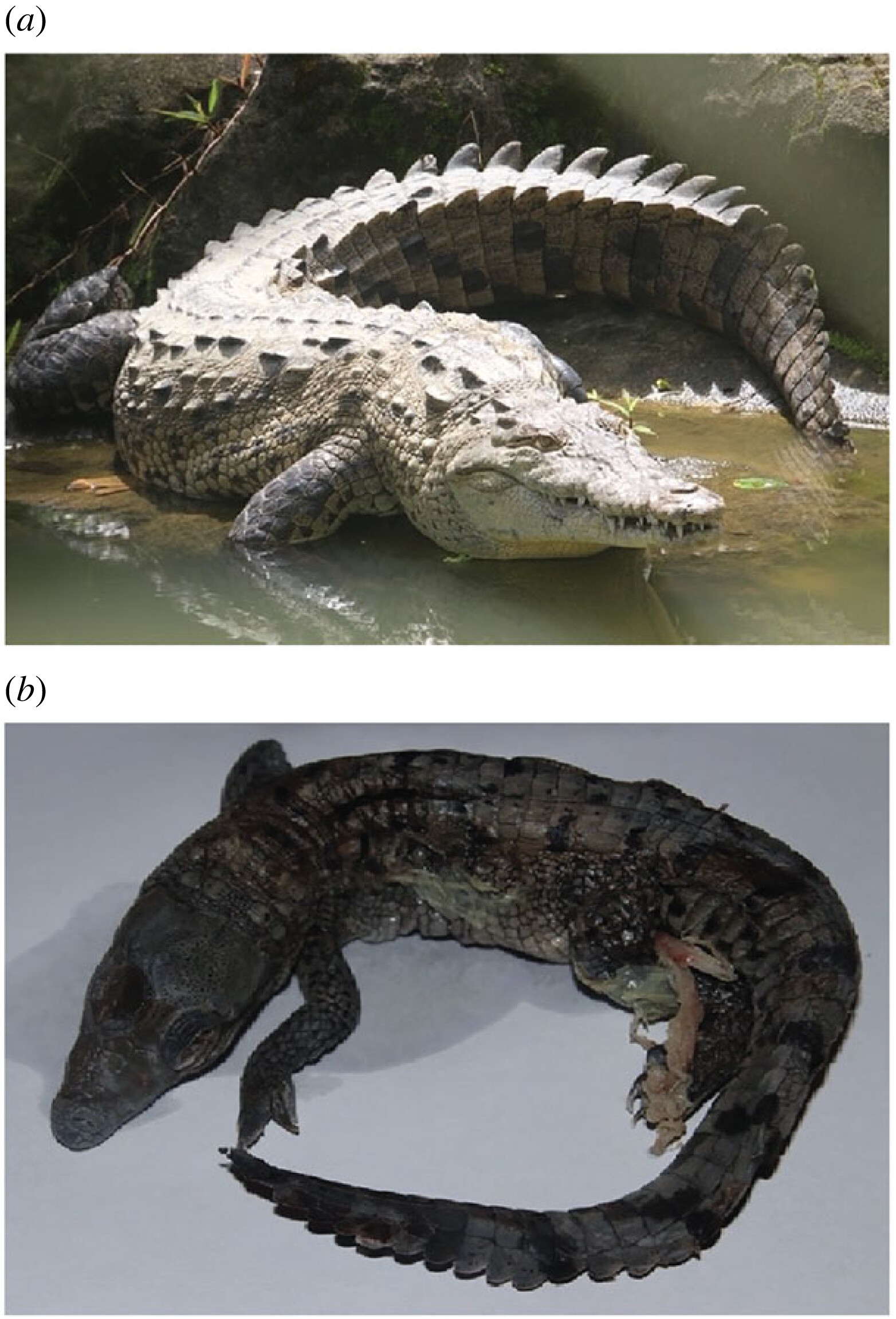

The female crocodile in question was kept on her own for 16 years in a zoo in Costa Rica. During this period of isolation, without any contact with male crocodiles, the female crocodile managed to reproduce and lay a clutch of 14 eggs, which were artificially incubated. Although the eggs failed to hatch, there was one that contained a fully formed foetus. This foetus was genetically identical to its mother and had no genetic material from any males.

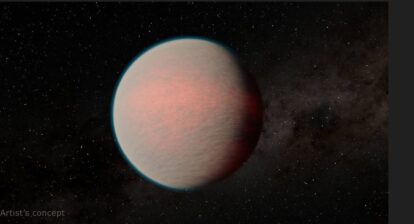

Figure 1. (a) Adult American crocodile, Crocodylus acutus. Photo courtesy of Q. Dwyer. (b) Stillborn fetus of American crocodile, Crocodylus acutus, Parthenogen. Photo courtesy of Q. Dwyer.

What is parthenogenesis?

This reproductive phenomenon, known as parthenogenesis, allows females to give birth to offspring without fertilization from a male. It is an exceedingly rare occurrence in vertebrates, and this is the first time it has been observed in crocodiles.

The team of scientists studying this unique case was astounded by their findings. It challenges the conventional understanding of crocodile reproduction and sheds new light on the reproductive capabilities of these ancient reptiles. By closely monitoring the female crocodile’s behavior and conducting genetic analyses, the researchers confirmed that the eggs were indeed produced through parthenogenesis.

The discovery of virgin birth in crocodiles has significant implications for conservation efforts and captive breeding programs. It suggests that female crocodiles held in isolation may still have the capacity to reproduce and contribute to the survival of their species, even without male presence.

“Our results provide both novel and substantive evidence of FP in an extant archosaur, the American crocodile”, say the scientists, adding “As such, we now have evidence of FP in the two main branches of extant archosaurians: crocodilians (Pseudosuchia) and birds (Avemetatarsalia).”

Further research is underway to investigate the underlying mechanisms and genetic factors that enable parthenogenesis in crocodiles. Scientists hope to gain a deeper understanding of this extraordinary reproductive process and its potential applications in conservation biology.

As the team concludes, “…more work is required to fully test the evolutionary distribution and dynamics of FP across deeper evolutionary time, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the ancestral states and rates of FP across vertebrate lineages.”

Is it good for conservation?

Nevertheless, it is important to note that while parthenogenesis in crocodiles may offer a unique means of reproduction, it also presents challenges. One of the primary concerns is the potential lack of genetic variation among the offspring produced through this process.

Genetic variation is crucial for species’ long-term survival and adaptability to changing environmental conditions. It provides the raw material for natural selection to act upon, allowing individuals with advantageous traits to thrive and pass on their genes to future generations. However, in the case of parthenogenesis, the offspring are genetically identical to their mother, as they do not receive genetic material from a male counterpart.

This lack of genetic diversity can limit the species’ ability to adapt to new challenges or environmental changes. If the environment becomes unfavorable or if a specific threat arises, the absence of genetic variation may hinder the survival of the entire population. Since all individuals share the same genetic makeup, they would be equally susceptible to the same vulnerabilities and may not possess the necessary genetic traits to overcome adversity.

The potential consequence of reduced genetic diversity is an increased risk of extinction. A lack of adaptive potential can make a species highly vulnerable to disease outbreaks, habitat loss, or other detrimental factors. The long-term viability of a population relies on maintaining genetic diversity through sexual reproduction, which allows for the shuffling and recombination of genes.

Therefore, while the discovery of parthenogenesis in crocodiles is fascinating, it is crucial to carefully consider the implications it may have for the long-term survival of the species. Ongoing research and monitoring are necessary to assess the overall impact of parthenogenesis on crocodile populations and to develop strategies for maintaining genetic diversity and ensuring their continued resilience in the face of environmental changes.

Even so, the revelation of a virgin birth in crocodiles adds another fascinating chapter to the ongoing exploration of the natural world. It demonstrates that nature continues to surprise us with its complexity and ability to challenge our preconceived notions.

Read the full study here.