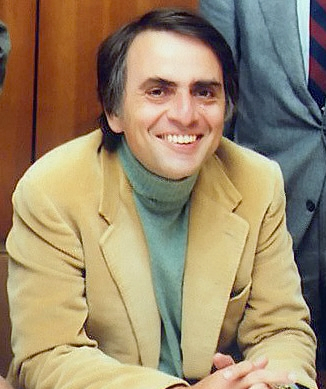

What is Carl Sagan Day?

Carl Sagan Day is an unofficial holiday celebrated on November 9th in honor of the renowned astronomer, astrophysicist, and science communicator. It was established in 2011 by the Carl Sagan Institute to commemorate his contributions to science and his tireless efforts to promote scientific literacy and public understanding of the cosmos.

Sagan’s legacy extends far beyond the scientific community, as he inspired millions through his popular books, television series, and public lectures. He was a passionate advocate for scientific exploration, space exploration, and critical thinking, and his work has had a profound impact on our understanding of the universe and our place within it.

Carl Sagan Day serves as a reminder of Sagan’s unwavering commitment to science education and public engagement. It encourages individuals to explore the wonders of the cosmos, engage in scientific discourse, and embrace the power of critical thinking in shaping a better future.

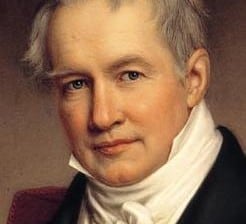

Carl Sagan, from image of the Planetary Society, cropped to size. CC BY

Who was Carl Sagan?

Carl Sagan was an American astronomer and planetary scientist who advocated scientific inquiry and promoted science communication. He was behind the series Cosmos that made so many kids interested in science – including me – and wrote many other books on science. He contracted cancer and died of pneumonia on December 20, 1996 at the age of 62.

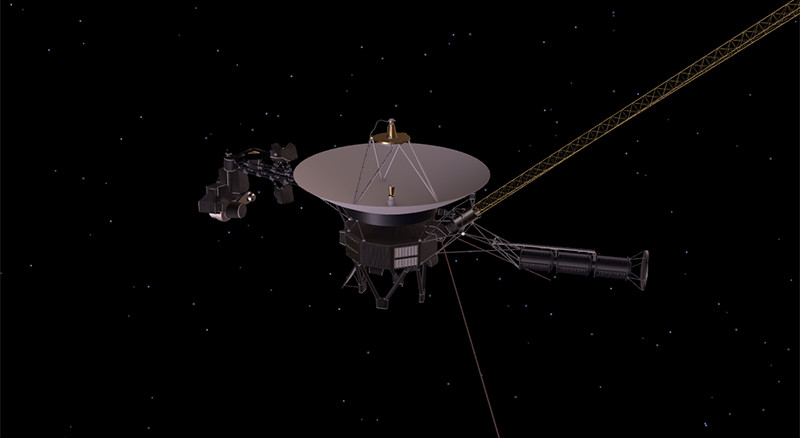

The Voyager Missions

It was the year 1977 and just eight years after human beings had landed on the moon that another epic journey began. Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 are robotic probes launched in 1977, whose primary mission was to study the planetary systems of Jupiter and Saturn. After making game changing discoveries, such as the active volcanoes of Io and liquid water oceans on Europa (Jupiter’s moons), imaging the complexities of Saturn’s rings, as well as studying the atmosphere of Titan, the mission was extended — three times.

Voyager 2 went on to explore Uranus and Neptune and is still the only spacecraft to have visited the outer planets. On its 41st year, it is now studying the outer reaches of the Solar System, currently travelling through the heliosheath. Voyager 1 began its journey out of the Solar System in 1980 and crossed the heliopause in 2012, becoming the first spacecraft to enter interstellar space.

The Voyager Spacecraft Model. Credit: NASA

According to NASA: “The Voyager spacecraft are the third and fourth human spacecraft to fly beyond all the planets in our solar system. Pioneers 10 and 11 preceded Voyager in outstripping the gravitational attraction of the Sun but on February 17, 1998, Voyager 1 passed Pioneer 10 to become the most distant human-made object in space.”

This illustration shows the position of NASA’s Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 probes, outside of the heliosphere, a protective bubble created by the Sun that extends well past the orbit of Pluto. Voyager 1 crossed the heliopause, or the edge of the heliosphere, in August 2012. Heading in a different direction, Voyager 2 crossed another part of the heliopause in November 2018. One of the annotated images below shows plasma flow lines both inside and outside the heliopause. The direction of the solar plasma is different from the direction of the interstellar plasma. The Voyager spacecraft were built by JPL, which continues to operate both. JPL is a division of Caltech in Pasadena. California. The Voyager missions are a part of the NASA Heliophysics System Observatory, sponsored by the Heliophysics Division of the Science Mission Directorate in Washington. For more information about the Voyager spacecraft, visit https://www.nasa.gov/voyage

The extended mission of both spacecraft is called the Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM) and its new objective is “to extend the NASA exploration of the solar system beyond the neighborhood of the outer planets to the outer limits of the Sun’s sphere of influence, and possibly beyond.”

The extended mission is expected to continue until 2025, when its radioisotope thermoelectric generators will no longer supply enough electric power to operate its scientific instruments. For now though, humanity’s farthest and longest-lived spacecraft are still in communication with Earth via a tracking station in Canberra, Australia.

Consider this for a moment though: the technology being used on both is from the seventies. Earlier, the two Voyagers transmitted photographs and scientific data from each planetary encounter. Now over four decades later, Nasa is still able to receive messages from 15 billion miles away, sent using an over 40-year-old, 12-watt transmitter (around the same as the light bulb in your fridge). This technology is not even close to what we use in our cell phones.

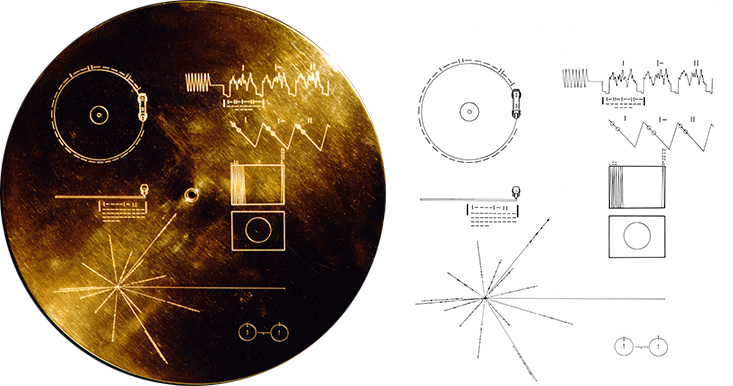

And that’s not all, each space probe carries a Golden Record of sounds, pictures, music and messages from Earth, selected by a committee chaired by the brilliant Carl Sagan — as well as directions to Earth, using a pulsar map, in case some alien civilization happens upon it and wants to find us.

The Golden Record cover shown with its extraterrestrial instructions. Credit: NASA/JPL

The Golden Record. NASA

We continue to have spacecraft orbiting the two planets that the Voyagers visited all those years ago. On July 4, 2016, after 5 years of traveling 1.74 billion miles (2.7 billion km), spacecraft, Juno, entered into orbit around Jupiter. Juno has sent back never before seen picture of Jupiter’s North Pole, which show storm systems and weather activity unlike anything we have encountered before. More excitingly, instruments also captured ghostly sounding emissions from the planet. The main objective of the Juno mission is to study the formation and evolution of the planet and gain an understanding of our Solar System. The observations will also help scientists understand other planetary systems. The mission was supposed to end in February 2018 but Nasa has extended the mission.

In 1997, we sent out Cassini, which reached the most beautiful planet in our Solar System — Saturn — in 2004. Cassini also had on board, a lander called Huygens, which landed on Titan, the largest of Saturn’s moons in 2005. It was the first landing ever on another planet and Huygens sent back important data from Titan, such as the existence of liquid hydrocarbon lakes.

(Check out the podcast on Cassini)

After almost 20 years out there, the Cassini Mission plunged into Saturn on September 15, 2017.

Cassini ended in 2017 and Juno will too, soon. But the Voyagers, undoubtedly our greatest space mission, will continue their journey towards deep space. They have given us many moments of amazement. Perhaps the greatest one was when Voyager 1 turned its camera back towards the Earth to capture the entire Solar System — it was Carl Sagan’s idea — where Earth can be seen as a single pixel pale blue dot. Just a dot — in the entirety of the universe.

He said: “Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every “superstar,” every “supreme leader,” every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there–on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam.”

THE PALE BLUE DOT OF EARTH “That’s here. That’s Home. That’s us.”Image: NASA / JPL

Who knows what new wonders the Voyagers, and other spacecraft that we have sent out, have in store for us?

Featured image: The Pale Blue Dot, NASA