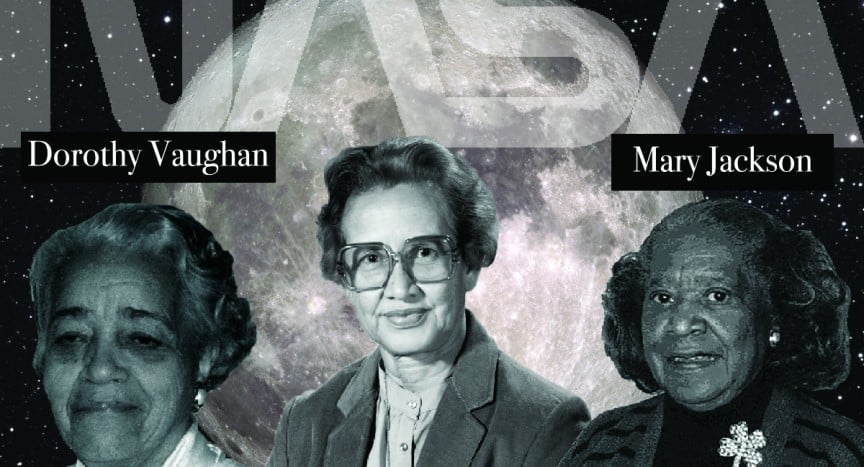

One small step for a man, a giant push from the women behind him – How a group of unsung women heroes helped NASA achieve its goal of putting a man on the moon.

On July 16, 1969, NASA launched Apollo 11 on its journey to the moon. Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, who were in that spacecraft were destined to be remembered for perpetuity.

(Check out the podcast on the 50th anniversary of the moon landing).

This launch was part of the cold war space race; the culmination of many previous efforts by both the Russian space agency and NASA to ensure that humanity visits its closest neighbour. Almost 400,000 people worked at all parts of NASA’s mission to ensure that everything went according to plan.

Among these were women — known as NASA’s computers. The story begins at the brink of the Second World War, when the need for aeronautical advancement demanded the appointment of mathematicians. Women mathematicians became the solution, and many were recruited into the Langley Memorial Aeronautical Laboratory (part of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, NACA) in 1935, for number crunching – acting as human computers, primarily because they were available and they did not have to be paid much.

In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt issued an executive order, which banned “discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries or government because of race, creed, colour, or national origin”, in order to increase the workforce.

Six months later, after the attack on Pearl Harbour, NACA began to hire African-American women with college degrees to work as the human computers, who came to be specifically known as the West Computers. Three of these were Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson. Even though they had the same education as the others, they had to retake college courses and were not considered for promotions or even other jobs within NACA.

Katherine Johnson was born in 1918, in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia and was interested in numbers and mathematics right from the start. In her hometown however, school for African-American children stopped at the eighth grade, so her father moved the family 120 miles to Institute, West Virginia, where his children could pursue a higher education. He placed his family in rented accommodation while he traveled back and forth between White Sulphur Springs and Institute for his job. He did this for eight years while all of his children completed their education. Katherine graduated high school at the age of 14 and from West Virginia State College at 18.

Katherine worked at NACA (which later became NASA) for three decades and her accomplishments included calculating the trajectories for Alan Shepard’s 1961 spaceflight, making him America’s first human in space and John Glenn’s first American orbit of Earth. Most importantly, she not only calculated the trajectory of the Apollo 11 journey to the moon but also worked on the plan that brought back the crew of Apollo 13, safely back to Earth. She was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2015 by President Barak Obama.

Mary Jackson graduated with dual degrees in mathematics and physical sciences and was hired to work at Langley in 1951. She worked as a human computer for several years, subsequently working for senior aeronautical research engineer Kazimierz Czarnecki, who encouraged her to become an engineer. This meant that she needed to take after-work courses at the segregated Hampton High School. She petitioned the City of Hampton and won the right to study next to her white peers. She graduated and was became NASA’s first African-American female engineer in 1958 — a title she held alone for pretty much all of her career. In June 2020, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine announced that the agency’s headquarters building in Washington, D.C., will be named after Mary W. Jackson, the first African American female engineer at NASA.

Dorothy Vaughn was a mathematician and became NACA’s first black supervisor in 1948. She worked for NASA for 28 years and specialized in flight paths and subsequently learned FORTRAN computer programming and taught it to her co-workers. She contributed to the space programme by working on the Scout Launch Vehicle Programme (launch vehicles designed to place small satellites into orbit around the Earth).

The precise calculations these women(and the other human computers) made, contributed much more however. They sent Voyager to explore the solar system (which it is still doing after over 40 years) and wrote the C and C++ programmes that launched the first Mars rover.

More Fantastic Women: Ada Lovelace, Mary Anning and Cecilia Payne Gaposchkin

![The Great Dark Spot (top), Scooter (middle white cloud),[97] and the Small Dark Spot (bottom), with contrast exaggerated.](https://www.360onhistory.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/Neptune_storms-414x224.jpg)